What would you do if you found a way to make high-quality insulation material by fermenting plant residues? Exactly. Submit it to a design competition and try to bring your innovation to market. Sounds logical right? There’s just one problem: it usually doesn’t work out or takes a very long time. And so your world-improving innovation goes to waste. Even if you win an honourable design award, you don’t succeed in getting your invention onto the market and thus into society.

- Unthinkable Marketing

Socially speaking, it is important that innovative, sustainable materials are put into use on a large(r) scale to help realise the transition to a sustainable world. This is therefore the main reason why many designers focus on the (further) development of bio-based materials: products made from regrowable, often plant-based materials as opposed to fossil, non-renewable materials. These designers want to make the world more sustainable and have good ideas. Innovative biobased product designs regularly win awards. However, the necessary step towards broad societal impact is not taking place. This is frustrating for the designers and detrimental to society.

Is there anything that can be done about this?

To see if something can be done about this, we previously conducted a study in collaboration with ClickNL entitled ‘From Award to Impact: Creative solutions for the biobased transition’ in which we investigated the societal impact of designers of biobased materials and products. We found that this impact is much lower than hoped and desired. This is mainly because it turns out that, in practice, there is really only one way to make social impact as a designer of biobased materials: commercial success in the market. In other words, if designers fail to sell their biobased innovations through the market, they have no impact. And it is precisely this commercial marketing that proves problematic in practice.

Indeed, there appear to be clashing interests on several fronts. If a designer-entrepreneur knocks on an existing manufacturer’s door to rent a machine or production space, it does not benefit. Existing manufacturers and governments shy away from disinvestment and capital destruction and therefore find it difficult to switch to new biobased products. And governments often see new biobased designs as risky because they are not yet proven in the long term. As a result, they are reluctant to issue licences.

So while designers find that making impact through the market often does not work well, it nevertheless proves very difficult to get away from it, to think outside the current (economic) system and to develop alternatives to make impact. This frustrates them because they are convinced that the move to an alternative economic system is necessary. First, because the current system encourages overconsumption. Second, because it offers few earning opportunities for sustainable designers.

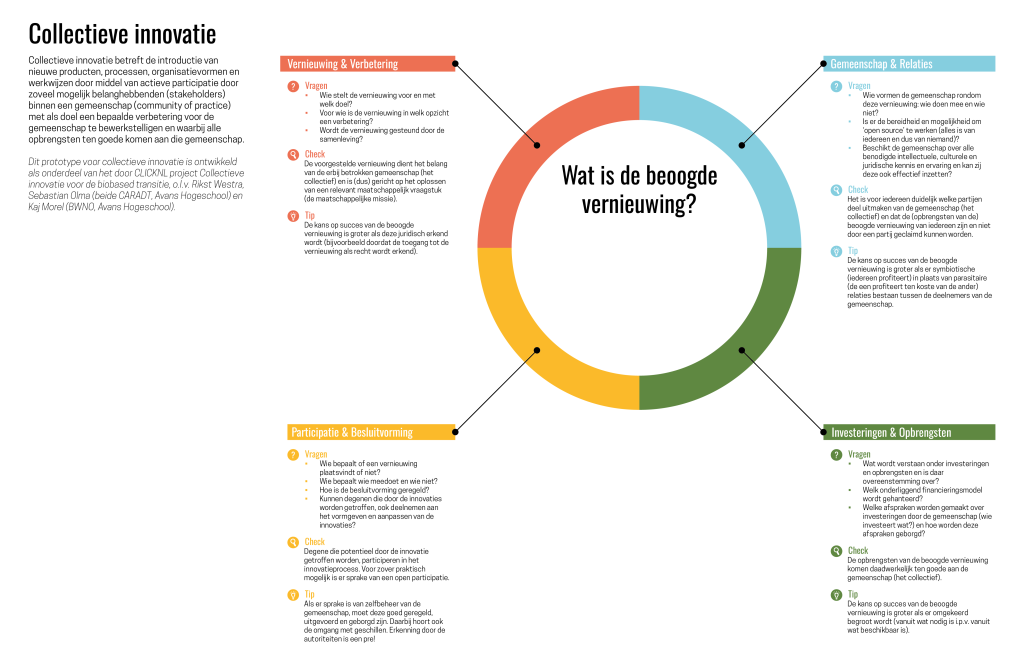

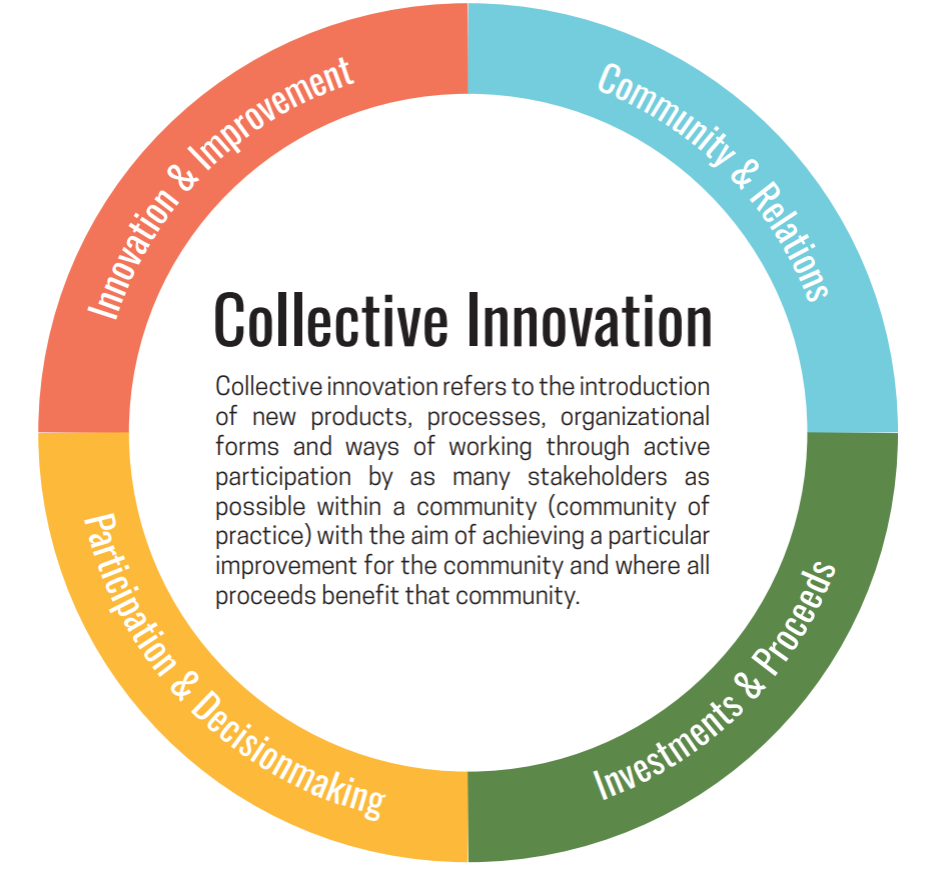

To get out of this impasse, we worked with the designers who participated in our research to see if there are other, more effective ways for them to make impact. This revealed that a more promising way to make impact is to develop infrastructures and programmes for forms of innovation where everyone sits around the drawing board with each other from the beginning. This also implies a redefinition of roles and ownership. We have called this form of innovation collective innovation and drafted the following working definition for it:

Collective innovation refers to the introduction of new products, processes, organisational forms and ways of working through the active participation of as many stakeholders (stakeholders) as possible within a community (community of practice) with the aim of achieving a particular improvement for the community and where all proceeds benefit that community.

Does collective innovation offer a solution?

In the follow-up research we are currently working on, we are delving into the question of what exactly collective innovation means with the aim of designing an effective practical approach to collective innovation – a prototype – with a focus on the biobased transition.

First, together with our partners -makerspace SPARK Campus in Den Bosch, cultural incubator Electron in Breda, urban development initiative Haus der Materialisierung in Berlin, creative studio Biobased Creations in Amsterdam and the Dutch Design Foundation in Eindhoven- we explored existing approaches such as open innovation, disruptive innovation, co-creation innovation, social innovation, and consortium innovation. We linked these to alternative economic approaches that emphasise the collective such as governing the commons, economic system innovation, and community wealth building. In addition, we looked at some well-documented case studies that provide inspiration for collective innovation such as some Dutch incubators and sanctuaries but also international cases such as L’ Asilo in Naples and Can Batllo in Barcelona.

Based on this input, we developed a concept prototype that we will explain further below. We are further developing this prototype in two ways. First, we will test it in practice in working sessions with our partners and their networks, the so-called PIPA workshops. In addition, we will discuss the prototype with innovation experts from science and research. On the basis of the reactions and insights from the PIPA workshops and expert discussions, we will arrive at an improved prototype at the end of this study of which both the content adequacy and the practical applicability have been tested on a small scale.

From PIPA to IIPA workshops

PIPA is a particular key methodology that stands for Participatory Impact Pathways Analysis, a structured practical approach to action research on change processes in which all stakeholders in an issue jointly develop a theory of change and impact pathways (ways to achieve that change) [1]. While a classic PIPA is mainly about developing a commercial service or product, we take a more-than-market (more-than-market) approach. That is, in designing our specific workshops, we have assumed that the development of innovations with a positive impact for the public good is best designed as inclusive societal processes. Hence, we need to look beyond potential producers and consumers of product or service innovations. We therefore call these workshops not PIPA but IIPA: Inclusive Impact Pathways Analysis. IIPA workshops involve a broad spectrum of societal stakeholders: initiators and potentially involved citizens as much as policymakers, commercial parties, scientists, artists, activists and (citizen) experts.

For many of these parties, time and money are limited. The participants involved often cannot afford to participate unpaid in a multi-day workshop like a PIPA . Therefore, in our IIPA workshops, we adopt a ‘quick-cook’ variant that particularly focuses on the development of the prototype as a synthesis of change theory and impact pathways in one and offer participants a fee.

The prototype

The structure of the IIPA is largely determined by the Collective Innovation model developed specifically for this purpose. Since the model is under development, we talk about a prototype. Central to the prototype is the intended innovation, because that is what it is all about. Around it are four pillars: these are the touchstones for collective innovation by which to determine the extent to which collective innovation actually exists. Slightly simplified, this involves the following questions (represented within the four pillars of Collective Innovation):

- What innovation is being pursued?

- By which community/relationships is the innovation supported?

- How is decision-making within the innovation process?

- Who funds the innovation and how are the revenues distributed?

Each pillar is elaborated into a few sub-questions, a tip and a check to focus and facilitate the conversation about it.

Using the prototype is simple. The intended innovation is entered in the middle circle, e.g. ‘roof tiles made of flax’. By now going through the different pillars one by one and answering and discussing the questions, checks and tips, on the one hand, a picture emerges of the extent to which the envisaged innovation can actually be categorised as a collective innovation and, on the other hand, an insight is gained into what is needed to make the envisaged innovation a collective innovation (thereby increasing the likelihood of successful introduction into society, as is our assumption).

Initial findings

The first two IIPA workshops highlighted a number of issues:

- The prototype works well to have a structured conversation about the case of collective innovation at the heart of IIPA;

- Providing a clear definition of the collective innovation envisaged is not easy in practice. This is partly due to the complex nature of more-than-market innovations of which Spark Innovation Campus and Haus der Materialisierung are examples;

- It appears to be possible to go through the model in the duration of the workshop, but time is limited and sometimes there is a need for a more in-depth conversation about certain parts of the prototype;

- Nevertheless (points 2 and 3), participants indicated that they felt the workshop was valuable, that the prototype was useful and provided new insights, and that it would be recommended to develop it further into an even more accessible and easier-to-use ‘toolkit’;

- The partners in the project also indicate that they learn a lot from the IIPA workshops and the use of the prototype and, at the same time, have useful suggestions for adjustments and improvements.

The sequel

The research project is now about halfway through. We are still going to do the following:

- The IIPA workshops at Biobased Creations

- Testing the prototype in collaboration with innovation experts and Building Balance

- Preparation of final report

- Presentations at Dutch Design Week and for politics, science and civil society in Berlin

Our impact

We are convinced that there is a role for the creative sector when it comes to developing innovations for a more bio-based, circular and sustainable economy. At the same time, it is becoming increasingly clear that a commercial, market-oriented approach alone is not effective enough to achieve a mission-driven economy. Therefore, the aim of this project is to stimulate and accelerate the bio-based transition by finding more inclusive and participatory forms of organising innovation. The impact of the project can be measured by the extent to which it succeeds in providing a workable prototype for collective innovation. In a follow-up project, we aim to turn this prototype into a toolkit for practical application.

Participants of this project are:

- Sebastian Olma, lector Cultural and Creative Industries, Centre of Applied Research for Art, Design and Technology, Avans University of Applied Sciences

- Kaj Morel, lector Unthinkable Marketing, Centre of Expertise Wellbeing Economy and New Entrepreneurship, Avans University of Applied Sciences

- Rikst Westra, researcher Centre of Applied Research for Art, Design and Technology, Avans University of Applied Sciences

Want to know more, respond or join?

Contact Rikst Westra at ra.westra@avans.nl.

[1] A more detailed explanation can be found here: http://pipamethodology.pbworks.com/w/page/70283575/Home%20Page